Spring, 1892

The foggy mist was still cool enough in the morning to raise the hair on Pleasant’s arms, but it was finally warming up enough that he could leave his coat in the house when he came out to work. A few minutes of planting in the tough soil of the Ozark hills would work up a sweat anyway. Pleasant dug his toes into the damp earth, enjoying the feeling of the soft ground and the sound of the cicadas buzzing in the woods around him. The farmland of Pyatt Hollow was not the most fertile, but there were plenty of hands to work it. The Pyatt family was enormous – Pleasant had over fifty first cousins alone – and they spread across the peaceful land of Pyatt Hollow for miles, working the land and coming together once a week under manmade brushy arbors for old-time religious worship. This land meant everything to his family, and Pleasant – still just a teenager – fully understood the privilege of working it. Like many of his cousins and siblings, he had left school at an early age – just fourth grade – to go to work doing what he loved, farming.

“Hey, Redbud,” his father came up behind him with the mule, using the nickname Pleasant’s family had affectionately given him because of the tinge of red in his hair, a rare trait in the Pyatt family. “Can you take the mule out back and haul some of that wood?” Pleasant loved his father, Daniel, who had been instrumental in the establishing of Pyatt Hollow. Pleasant took the mule’s lead and started to head out back, but paused.

“Pa?” Pleasant was as serene as the misty morning. “Do you figure we’ll have a good season?” Pleasant was hoping for good luck, not just for the family but for himself, as he had a few other things on his mind besides plowing and fertilizing the land for the summer. He had taken up with a local church girl, Mary, and she had confidently told him (in that strange prophetic way she had) that they would soon be married and start their own family. He wasn’t inclined to disagree with such a pretty woman, and so he’d hoped there would be some extra time to make the wedding plans. A good season would ensure that he’d have the extra time to focus on such matters.

Daniel chuckled, reading his son’s face. “Eager to get on with it, are you?” He grinned. “Yes, I think it will be a good season. The land is rich and the weather has been great. I’m glad, you know? We’ve been working so hard, and that hard work should see us through this year.” Pleasant smiled and patted the mule; she smelled a little sour this morning, so he’d rinse her off when he put her in for the evening later. “Redbud,” Daniel continued, “I’m glad you enjoy the work of the farm. I have big plans for this place.” He pointed towards the dirt road leading to the heart of Pyatt Hollow. “I want to build a church out there, so we can all gather even when it’s raining or cold. I hope you’ll help me get that done.” Pleasant had heard his father talk about the church often and was pleased to hear that it was finally time for building. Maybe he could wed Mary in the new church. He imagined standing there at the altar with her, his father (a Reverend as well as a farmer) performing the rites with his mother and dozens of Pyatt cousins, sisters, and brothers there to celebrate with them. He felt a light thrill in the region of his stomach at the thought, and headed hopefully to the woods.

Summer, 1933

The sun was relentlessly beating down on the dry ground, and Pleasant’s neck and shoulders radiated with the heat of the day. The fifty-something man had spent many summers working in these fields and grounds, but he had never seen them look so barren and thirsty. He stopped his work to take a break, leaning on the buckboard wagon he’d built maybe ten years back, its wood weathered from years of use. Mildred Bailey’s sultry voice filtered out of the farmhouse from the radio they’d bought on installments. “You took the part that once was my heart….so why not take all of me?” Times were difficult in Pyatt Hollow. The great depression was upon the entire community, and an awful drought had dried up the crops; it was a daily struggle to keep the farm alive, and families had to band together to survive. In that farmhouse were three near-to-grown children and two granddaughters to feed. Pleasant felt frustrated with the knowledge that he might not be able to keep food on the table for long. He kicked the wheel of the wagon out of frustration, the splintered wood cracking further as the pressure of his leather boot did its damage. Pleasant, who generally lived up to his name, wasn’t one to let his temper show, but this great depression was taking its toll on him.

“Don’t be breakin’ yer foot now!” called a masculine voice, cutting into the tension of the moment. A couple of small covered wagons were parking at the fence line. A grin broke out on Pleasant’s face as he saw his visitors – Ralph Blakely, Pleasant’s oldest son Roe, and the Vauls – all piling out of the wagons with weary smiles, shaking the dust out of their clothes. Pleasant felt the weight of the day lift slightly as he moved to greet his friends and family. There had been precious little to celebrate in the last few years, but the sight of loved ones brought a much-needed respite to his mood. Pleasant’s wife Mary had anticipated the arrival of the guests as usual, and appeared as if from nowhere with a canteen of water and some hoecakes, apologizing for the meager fare. They sat around a while, sharing stories and talking about the drought.

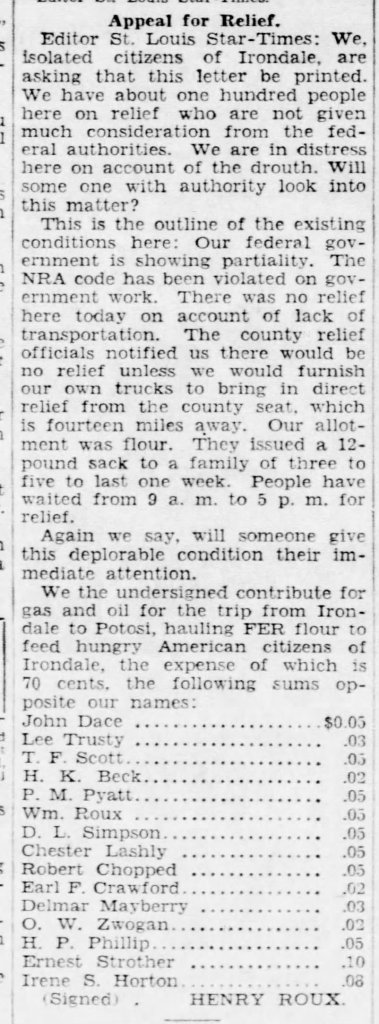

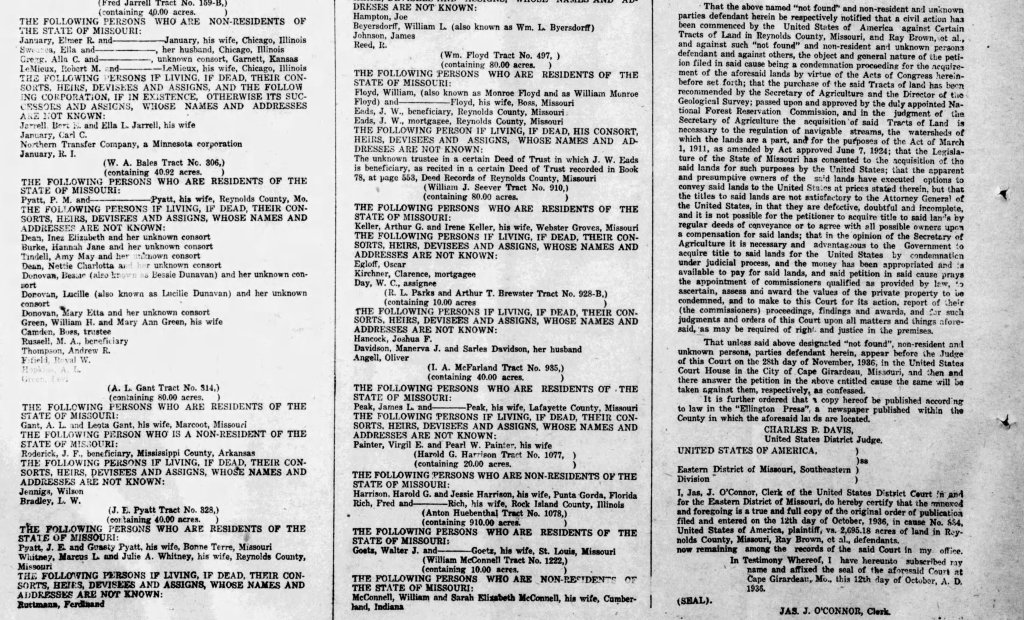

Ralph leaned back against a tree and sighed. “Heard some of the men from town are planning to write to the government again.” Pleasant nodded solemnly. The letters to the government requesting aid had been printed in the papers, and not without response. But the aid had been trickling in so slowly as to barely be worth mentioning.

“It’s awful,” Pleasant offered his opinion. “The help they promised us ain’t coming, not unless we somehow make it all the way out to the county seat to collect it. And they know most of us don’t have the gas or the money for that kind of trip.”

Ralph nodded, his jaw working. “What do they expect us to do? Sit here and watch our families starve?”

Pleasant shook his head, helpless. “So what’s in the letter this time?”

Ralph watched the children run around the fenceline while they talked, his concern for the family obvious. “Henry Roux and some others got a harshly-worded letter ready, asking for someone with authority to actually take a look at what’s going on out here. A group of ‘em are putting some pennies together to cover the gas and the oil for the trip to Potosi, just so they can haul back the little bit of flour Uncle Sam’s offering.”

Pleasant was proud of his neighbors – willing to work hard but brought to the pitiful act of begging for scraps. Without that flour, he knew some families might not make it through the season. The thought twisted in his gut. He would sign his name to this appeal and donate what little he had, holding onto a thin hope that help would come in time. He gazed at the sky, looking for what little cloud cover might come and provide some blessed shade from the boiling sun, and said a silent prayer. “Lord, I don’t know if you’re listening, but these are awful hard times and we sure could use a break.” He glanced over to Mary. She always seemed somehow to know what was coming, and the lines of her face only revealed harder times to come. He grasped her hand, wondering if they would make it through. The brutal summer was testing them all, but they were tough. They wouldn’t break, not yet.

Autumn 1934

Pleasant’s daughter Pearl, 32 years old, stood silently in the corner of the smoky living room, clutching the charred remains of the feathered halo that was the only reminder she had left of her recently-departed baby Lindell, as Pleasant and Mary picked through the disaster. Pearl’s house, situated on the bluffs along Missouri’s Big River, had succumbed just hours before to a devastating house fire that had caught as Pearl had been preparing the morning’s breakfast. News of the fire had taken a few hours to reach Pleasant; by the time he’d gathered up the family in the wagon and made the dusty journey to Pearl’s place on the Big River bluffs, the flames had long since died down, leaving only the ashy remains. The fire had consumed nearly everything, leaving only the bits and pieces out on the front lawn that Pearl had managed to rescue. Pleasant saw Mary take Pearl aside, whispering to her. “I suppose now we can move closer to Pyatt Hollow at least,” Pearl was saying. “Maybe Jerdon Town.” Mary nodded helpfully and continued opening drawers and cabinets, looking for items that could be loaded onto the wagon for salvage.

Pleasant wasn’t unhappy with this idea. He loved his family, and loved them better when they were close by. The depression had hit everyone hard, but somehow they were making it through. The letter he’d signed to the government last year had finally gotten some attention, and relief was coming a little steadier now. News had come from town that farmers like him could apply for drought relief loans. It wouldn’t be much, but it might just help them scrape through the winter and into the next year. Maybe their luck would turn. Pleasant gently pushed a burned-up stool aside and picked up a small side table, assessing the damage. It had been a tough road, but there were memories, and there was family. Renewal had to be right around the corner.

Winter, 1940

The bitter cold wind of December swept across the empty fields where Pleasant’s land used to stretch. Once prosperous and full of potential, Pyatt Hollow had been consumed by the depression and the needs of the broader Ozarks community. “Eminent Domain,” the lawyer had said to him, going over the paperwork in a blandly-heated office that smelled of printer ink and the quiet shame of a man doing the government’s dirty work. Their land was being seized for community development. Pleasant had thought that Pyatt Hollow was a developed-enough community, but what did he know? Having worked the land for sixty years, he had plenty of farming skill but no fancy vocabulary to argue his case. Words like “public good” felt hollow coming from the lawyer’s mouth – he had never touched the soil or broken a sweat in the sun. Pleasant walked the boundary one last time, his footsteps crunching on the frozen ground. He trampled on a surveyor’s stake, remembering the years of hard work he had spent making a home here for his family.

Mary ran her hand down his back, rubbing gently. “It’s all right, Redbud,” she whispered. “It’s just dirt. The important thing is the memory. We’ll be okay. Jerdon town is just as good, and our daughters are there.” Pleasant knew she was right, but he felt sad nonetheless. He took a last look at the land he had worked so hard to keep, and turned away, defeated.

The next few years represented a quiet burial of life in Pyatt Hollow as it had been known. Pyatt Hollow church closed down, replaced by a fancier, newer model dubbed “Center Ridge Baptist” up the road. Pleasant had thought that the old church would stand forever. Siblings, brothers, and cousins were similarly displaced, but kept their close connections, visiting regularly to keep up the relations. Pleasant watched as Pearl raised her family, raising eleven children under one small roof. Life was different, but not altogether bad. There was a lot of love to go around. The depression lifted, and prosperity began to sneak back into the town, especially as the lead mining and timber industries started to boom with the arrival of a new railroad.

But then little grandson Oscar got sick, and Mary made her damned prophecy. “Oscar will not die,” she had said, and then predicted that one of them would go in his place. Two days later, when walking through the woods, Mary had trampled on a snake and succumbed to its bite. If anything represented the end of the Pyatt way of life to Pleasant, it was losing his wife. After her funeral, he returned again to their old tract of land and watched the slow construction of new buildings going up. Standing alone in the woods, observing from afar, Pleasant felt the grip of winter settle around him. Spring was coming, but would he have the strength to face it, to start over again?

Spring, 1942

Reverend Pleasant Pyatt stood at the pulpit of Center Ridge Baptist, his hands smoothing the new finish of the wooden lectern. The church still smelled new. It had taken a few months of gentle coaxing by his family before Pleasant would attend, but now he was fully invested in the growth of this church as one of its rotating roster of ministers. The building may be new, but the people sitting in its pews were as familiar to him as his own family. His heart swelled as he looked at the familiar faces, their smiles encouraging him as he preached the Word of God.

There was his daughter Pearl and her husband James, sitting in the second row with a half a dozen children in tow, and further back, his cousins and neighbors who had been with him through countless hardships. And there were new faces too, young families, some friends who had come to settle in the area – and a breathtaking woman that looked to be about his age sitting in the back pew, holding his gaze steadily as she sang boldly along with the congregation to Blessed Assurance. A spark of something unexpected took hold in his stomach, a welcome feeling, a promise of a new chapter, a new season of life ahead.

Coda: This story is embellished but based on actual stories passed down in the family and documents left behind in genealogical and historical archives. You can read more about this website here: About the Site

Leave a comment