Business at the Creamery

The pale orange sunrise broke over the faded barn on a cool Iowa morning in 1900, casting long shadows across the Mitchell family’s modest farm in Cerro Gordo. Fifteen-year-old Dale Mitchell squinted against the light as his father Owen hitched the wagon, the clink of the metal echoing in the morning stillness. When the horses were finally ready, Owen climbed up and flicked the reins, setting the wagon on its journey into town.

When they arrived at the Garner Cooperative Creamery, Owen and Dale unloaded their haul of metal milk cans. Owen’s back complained against the heavy cans – 49 years of farming had not been kind to him. The creamery foreman greeted them with a broad grin. “Morning, Owen. More Jersey cream?”

Owen nodded, hiding his pride. “It’ll do ya.” Jersey cows were a little smaller than your standard Holstein but they sure were good at making that butterfat. The foreman tipped his hat and tested the cream, spinning the golden liquid in a hand-cranked centrifuge. The butterfat rose to the top in a thick band, and he gave an approving nod. Owen was glad – he had worked very hard over the past decade to build up his farm’s reputation for producing quality cream. His livelihood hinged on the trust of these local buyers.

On the way home, Dale asked, “Pa, why don’t we sell all the milk instead of just the cream? We make so much, it seems crazy not to sell it all.”

Owen chuckled. “Son, a can of cream gets us twenty dollars. A can of milk? Barely a single dollar. Cream’s worth more and it’s easier to haul. That’s why we use the separator back home—it keeps the work smart, not hard. And the skim’s not wasted, we give it to the pigs.”

Dale nodded, grinning a little at a joke he just thought of. “Is that why they say the cream rises to the top?”

Owen grinned back. His son was funny. “That’s us, son. Rising to the top.”

Back at home, Ella stood in the yard, pinning laundry on the line as little Glenn toddled around her, arms full of clothespins. Owen smiled at the scene as he pulled the wagon up close to the yard. Life was good—better than he’d ever hoped. If they were rising to the top, he imagined there was no limit to how high they could go.

Work Smart, Not Hard

Owen had been working on his legacy his whole life, it seemed. His grandfather, Abner Mitchell, loomed large in family lore—a pioneer who cleared the Wisconsin wilderness, raised thirteen children, and left behind a hundred or so grandchildren. Among the sprawling Mitchell clan, carrying on the family name became something of a competition. Owen’s siblings made their marks in bold strokes: brothers marching off to fight in the Civil War and later the Spanish-American War, and sisters establishing themselves as dressmakers, artists, and philanthropists.

Owen, however, took a quieter route. He built his life on a modest farm near Clear Lake in northern Iowa. When their father, Jesse, passed away, the Mitchell family dissolved into a bitter squabble over the inheritance. Owen wanted no part of it. “I’ve no truck with legal fights,” he’d said, not knowing the irony of that sentiment would haunt him later.

Without a share of Jesse’s estate, Owen had to scramble for every penny. Winters were especially lean, so he spent months in Michigan’s lumber camps, felling trees in the biting cold. The work was grueling, but Owen never lost his sense of humor. He learned valuable lessons there: strength alone wasn’t enough; success required working smart, not just hard.

When he returned to Iowa after his final winter in the forests, he surveyed his farm with fresh eyes. Farming row crops alone wouldn’t cut it—he needed a new approach. The burgeoning dairy industry in Iowa caught his attention. Cream was in high demand, and it seemed just the ticket for his family’s success.

After Dale had grown up a bit and learned the trade, he joined his father. One day, he introduced Owen to a professional-looking pair of local cattle traders, who promised to help him get a boost with the sale of some fine cattle.

“They’re sound and all right in every particular, and with calf,” the men, James and Edwin Pinckney, had assured him about the two dozen cows they were selling. It seemed like the perfect opportunity to launch a cream business. Owen shook hands on the deal and set to work, investing in another cream separator and other supplies to prepare his farm for this expanded venture.

For a while, it seemed like things might work out. With his son Dale, Owen threw himself into the business, hauling cream to the cooperative and watching his reputation for quality product grow. But within months, cracks began to show in the foundation of his plans. The handshake deal wasn’t as sound as the traders had promised, and Owen would soon find himself embroiled in a legal battle that threatened to undo everything he had built.

The Manitowoc Pilot; 29 May, 1884

A Day in Court

The trouble wasn’t obvious at first. It started with a single cow—one Mr. Pinckney, the trader, had assured Owen was “with calf.” Owen had dubbed her Dandy, and at first, she progressed through her pregnancy as expected. But one day, Dale came running from the barn, his face pale. “Pa, something’s wrong with Dandy.”

Owen didn’t waste time. He was in the barn in an instant, his heart sinking at the sight before him. On the straw-covered ground lay a small, lifeless calf, no bigger than the dog snoozing on their back porch. Nearby, Dandy trembled, her body heaving with labored breaths. She looked rough, like she’d been through an ordeal.

“Damn it,” Owen muttered under his breath. “Dale, fetch the wagon and get the vet. Now. This is one of Pinckney’s cows, and I need to know if this is going to be some kind of problem.”

While Dale sprinted for help, Owen knelt beside Dandy, running a soothing hand along her flank. She was panting heavily, her head dipping low. When he could tell she was stable, Owen began to clean the barn with deliberate care, dragging fresh bedding in place and setting the calf’s body aside for examination. He thought of the other farmer in town who’d recently lost a whole herd of heifers to a disease that caused calves to be born early, usually dead. Contagious abortion, they called it, because it spread through the herd faster than the flu. The words had sounded ominous enough when he’d first heard them, but now they rang in his ears like a curse.

Owen’s chest tightened. He had invested most of his savings into these cows. Pinckney had given his word they were good stock—this was supposed to be the cornerstone of his cream business. His mind raced as he waited for the vet, each moment dragging longer than the last. When the vet arrived, he examined the calf and Dandy, giving Dale instructions to help the cow recover. Then he motioned Owen outside the barn to talk privately.

“I hate to say it, Owen,” the vet began, “but you’ve got good instincts, and it’s unfortunate. These cows do have contagious abortion. It’s not just Dandy you need to worry about — any of the others could be infected. None of them are likely to bear calves, and if you don’t isolate them, your whole herd could be at risk.”

The news hit Owen like a blow. Swiftly, he moved to separate the new cows from his existing stock, but the damage had already been done. Over the following weeks, the losses mounted. A few more cows aborted, and the milk yield from the herd dwindled. Each time Owen tallied the books, the profits looked worse.

Owen’s frustration grew. He had trusted the Pinckneys, and now his business and livelihood were in jeopardy. He wasn’t the kind of man to let an injustice go unanswered. Each evening after the farm chores were done, he and Dale sat at the kitchen table, debating their options. By the end of the month, they’d reached a decision.

Together, they traveled to the Winneshiek County Courthouse to file a lawsuit. The brand-new courthouse building was a marvel—its tall, imposing columns rose like sentinels, and the clock tower cast a long shadow over the town square. Citizens had grumbled about its expense, but to Owen, it was a testament to the community’s belief in its future – hope in opportunities yet unreached.

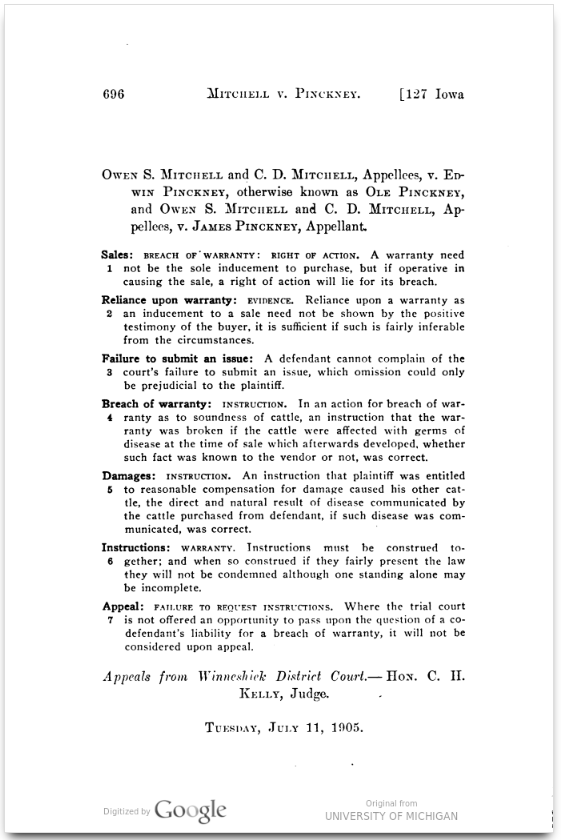

A few months later, the courtroom became their own personal battlefield. Owen and Dale faced, for the first time since the transaction, James and Edwin Pinckney, who claimed they were ignorant of the disease when they sold the cows. But the Mitchells’ lawyer argued well, and the evidence was damning—sick and dead cows, the resulting financial losses, and Pinckney’s verbal promise of the cows’ health. Owen himself testified, his voice steady despite the weight of his emotions. “He gave me his word, Your Honor. In our world, that’s as good as a contract.’ He paused, glancing at James seated across the room. “Or at least it should be.” James avoided his gaze.

The Pinckneys’ lawyer pushed back hard. James Pinckney hadn’t known the cows were diseased, he argued, and Edwin wasn’t even in town when the deal happened. Besides, no warranty existed—it wasn’t in writing.

Thankfully, the jury disagreed. They ruled in favor of Owen and Dale, awarding damages to cover their losses. Even as the jury announced its verdict, Edwin Pinckney sat stone-faced, his hands clasped tightly in his lap. Owen caught his glare as he left the courtroom, a silent warning that the fight might not be over. Owen waited until they were home to celebrate properly, raising a cheer with the family in utter relief. Rebuilding wouldn’t be easy, but with the compensation, he would be able to start a new chapter in their farm’s story.

But then, barely a week later, a letter arrived that gave Owen whiplash. The Pinckneys were appealing, and taking the case all the way to the Iowa Supreme Court. Frustrated, Owen crumpled the paper in his fist. “They’re not giving up,” he told Dale. “But neither are we.” He had once considered giving up this fight, but he kept remembering the promise that James had made him, and he just couldn’t let that slide. It was a matter of honor.

Winneshiek County Courthouse in Decorah, IA

A Supreme Ruling

It was a hot July day when the train pulled into the Des Moines station. Owen, dressed in his best church suit, wiped sweat from his brow as they approached the Capitol building. Dale, who had borrowed a jacket that didn’t quite fit, looked just as nervous as Owen felt. The grand halls of the Capitol were unlike anything they’d seen back home, the polished marble and sweeping staircases a reminder of the gravity of the moment. The golden dome winked a sunny reflection at them as they entered the building.

Inside the Supreme Court chamber, the tension was palpable. Across the room sat Edwin and James Pinckney. Edwin, the elder brother, was polished and professional, with the air of someone used to commanding attention. He cut an imposing figure, glaring out from the gallery through round rimmed glasses. James sat beside his brother in the courtroom, his suit sharp and his lapel pin—a polished silver emblem of his veterinary college—catching the light.

The Pinckneys’ counsel argued again: there had been no written warranty, and there was no proof that either brother had knowingly sold diseased cows. But the Mitchells’ lawyer pushed back, pointing to the verbal promise of good health—a promise the Pinckneys should have honored.

As the justices deliberated, Dale leaned close to his father. “Do you think they even know what this has cost us?”

Owen’s gaze drifted to the Pinckneys, and then his eyes closed briefly in silent prayer for a moment before he turned back to his son. He thought of the stress on the entire family over the past year as they had scrambled to keep the farm profitable. Then he grinned suddenly, remembering the little joke he’d shared with Dale all those months ago before this had started. “Maybe so, maybe not.” He gave Dale a small, reassuring grin and a wink. “But remember—the cream always rises to the top.”

In the end, the Iowa Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Mitchells, affirming the lower court’s decision. Dale maturely shook James’ hand as they left the building, ensuring there were no hard feelings to carry on. To his credit, James returned the handshake, though defeat was evident on his face. Owen and Dale were overjoyed, and the elder felt a weight lift from his shoulders as they left the courtroom. Before heading home, they stopped at a confectioner’s shop, buying a box of chocolates for Ella and licorice for the younger children—a little celebration for a huge victory. As the train carried them back to Cerro Gordo, Owen looked out over Iowa’s endless corn fields with his head held high. This wasn’t just a win for their family—it was a win for all farmers who worked with integrity and counted on the word of honor from their neighbors.

Coda: This story is embellished but based on actual stories passed down in the family and documents left behind in genealogical and historical archives. You can read more about this website here: About the Site

Leave a comment