An Important Apprenticeship: 1865

Stavanger’s newest church smelled of freshly-cut wood, and the sunlight bounced brightly off of the high beams inside St. Petri Kirke, where Jakob Olesen-Aase stood at the altar, holding the hands of his bride Frederikke. As she squeezed his hands reassuringly, he took in her beautiful round face, her ice-blue eyes exactly the color of the floor-length linen dress she wore, and smiled as the congregation’s voices swelled, singing Kjærlighet er lysets kilde – Love is the Source of Light. His thirty years living in Aase, a small community near Egersund, had brought him many joys and surprising twists – but he could never have predicted that his turn as a carpenter’s apprentice in Flekkefjord would lead to such an adventure. Frederikke was a young woman in the rather large Reiersen family that he was working for, and they soon fell in love. She shared his appreciation for adventure and his dreams of moving to bigger, more bustling locales – and so when he learned of the beautiful church being built in Stavanger, he asked her to come. She’d agreed, and they both had obtained notes from the pastors of their parish churches recommending them to St. Petri’s. Reverend Sagen had taken them in with a smile, and now he stood at the modestly-decorated but ornately-carved altar, joining their hands together in a marriage blessing.

St. Petri Kirke in Stavanger Norway – photo credit: domkirkenogpetri.no

The months following the wedding went by in a blink. Jakob approached the renowned architect Conrad Frederick von der Lippe – “Fritz,” as the locals called him – and flattered him with praise over the incredible craftsmanship and majesty of St. Petri Kirke. Humored, Fritz asked Jakob if he’d like to prove his mettle as a carpenter and employed him in the restoration of the old cathedral. By week’s end, Jakob was restoring pews, crafting arches, and learning from seasoned carpenters the tools of the trade that would turn him from an ordinary carpenter into a craftsman.

The work on the cathedral took many years, and in that time, he and Frederikke loved their life in Stavanger. The small city bustled with energy, its harbor teeming with ships bound for new worlds. Together, they had two sons – Otto and Martin. All in all, it was as good a start as any couple could have wished for to settle into a life in Stavanger – but Jakob’s spirit was stirring with a kind of restless ambition. Many of the new friends he had made while working were saving to emigrate, and they were encouraging him to join them on a journey to Nortamerika – the United States. Ships were leaving regularly from the harbor at Stavanger, and there was good work, much food, and vast tracts of land for emigrant families who were willing to work for it. Jakob’s parents had always scolded him for being impulsive – but this was too good an opportunity to pass up. He knew he would need Frederikke’s support for the idea to work.

One evening, as Frederikke rocked Otto to sleep, Jakob sat beside her and gently took her hand. “We can build a bigger life, a good one for our sons, across the sea.” She hesitated. He knew she was attached to her life here in Norway, but in the end, the promise of a prosperous life for their children convinced her. She had known Jakob was an adventurer when she married him, and it was part of why she loved him so. She nodded quietly, and turned her focus to her boys.

After months of saving and preparing, the day came. They boarded the Brodrene, Frederikke taking one last longing look at her homeland. Her hand rested on the curve of her belly – the next child would be born in another country, his eyes never having seen this one at all. A tear slipped down her cheek as she watched the busy harbor, St. Petri’s spire piercing the gray sky, a silent witness to their journey. As the horn bellowed and the ship cast off, Jakob gripped her hand reassuringly. Together, they turned toward the open sea, read to carve out their place in a new world.

Enhanced photograph of Bergen Norway 1856 – photo credit http://www.ntnu.no

Building Dreams in Chicago: 1872

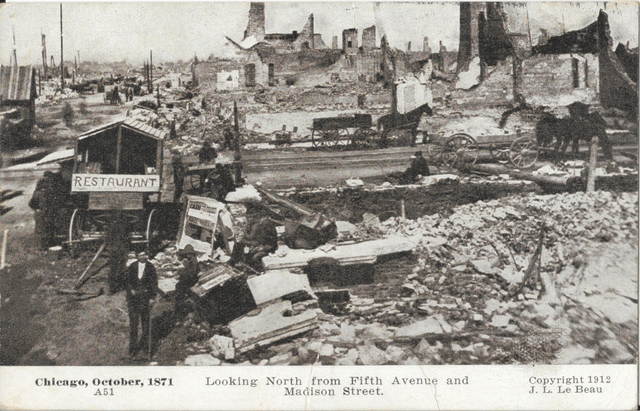

After arriving in Quebec, Jacob and Frederikke inquired about carpenter work and quickly learned of opportunity in Chicago. It had been a frustrating journey across the Atlantic – two toddlers and an advancing pregnancy had increased the couple’s desire to land in their new home. They were eager to set down some temporary roots, and the streets of Chicago offered promise of work and opportunity, a city clawing its way back to life after Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow set the Great Fire of 1871 on its destructive path. They made their way to Cook County so as to help rebuild what the great fire had laid waste.

Jacob, who Americanized the spelling of his name almost immediately to ease the naturalization process, found work easily, his training in Stavanger and the years spent restoring the cathedral highlighting him as a skilled employee. By day, he wielded his tools on scaffolding, crafting beams and frames with meticulous precision. By night, he returned to the family’s cramped lodging in an immigrant quarter, the air thick with the mingling scents of body odor and the unfamiliar cooking spices of the various immigrants with whom the family boarded.

It was here, in the heart of Chicago, that their third son, Fritz, was born. Jacob looked down at the child in Frederikke’s arms and smiled. “Jalmer Fredereick,” he said with determination, “But we’ll call him Fritz.” The name was a tribute to the architect who had helped him begin his career in Stavanger. Fritz’s birth was a bright moment in a city that otherwise felt bleak. The streets were loud and chaotic, and the air was heavy with soot from the endless construction. Frederikke was trying not to fall into despair, but she was desperately homesick. She stuck close to the other Norwegian immigrants and tried to focus on her family. She kept a small pot of wildflowers on the windowsill, a quiet rebellion against the city’s gray, industrial sprawl. On Sundays, the family joined other Norwegian immigrants at the Lutheran church, where hymns like “Jeg er en gjest og fremmed” (I Am a Guest and a Stranger) reminded them of home. But even the warm embrace of the immigrant community couldn’t mask their growing discontent. They longed to build something more permanent.

One evening, after a long day on the construction site, Jacob returned home to find Frederikke sitting by the window, Fritz cradled in her arms. The older boys, Otto and Martin, were playing quietly on the floor. She looked up at him, her face pale but resolute. “Jakob,” she said softly in Norwegian, “this isn’t the life we dreamed of. I miss Norway.”

Her words stayed with him. They had left Stavanger seeking a better life, but Chicago felt like a compromise—a city of opportunities, yes, but it was a distasteful life. Jacob began to talk to other immigrants about life beyond the city. Some had family in Iowa, a state where the land stretched wide and open. Together, Jacob and Frederikka decided to move West.

Jacob packed up his tools, and the family boarded a westbound train. As the city’s skyline faded behind them, Frederikke exhaled deeply, as if letting go of a weight she had carried since they arrived. The boys pressed their faces to the window, watching the endless fields roll by. For Jacob, it felt like a return to something familiar. Iowa’s quiet farmland reminded him of the rolling hills of Aase, and for the first time since they had come to America, the couple felt like they could love their home.

The Chicago Fire devastated the city and took years to rebuild. Photo credit: Wikimedia commons

Building a Legacy: 1900

Clinton, Iowa at the turn of the century was a rough, bustling river town – closer to the family’s vision of home but still a compromise. They had traveled far to trade Chicago’s dirty streets for the open skies and fresh air, but the streets were muddy and there was constant activity and problems from the barges traveling along the Mississippi River. After the birth of two more sons, Herman and Hartwick, Frederikke began to push Jacob to continue their journey further Westward. She longed for a taste of what she was missing back in Norway.

At long last, they found a better home: Emmet County, where a small but thriving Norwegian community was carving out their own spaces in the prairies of Northern Iowa. For $25 an acre, Jacob could purchase some beautiful farmland near High Lake, a shimmering expanse of water surrounded by rolling fields. It was exactly what they had been searching for. Once again, they packed up and moved, and finally began to settle in to home.

Jacob didn’t have the same skills at farming that he did with carpentry, but he gave it a shot, tilling the fields and planting corn. His sons pitched in, proving adept helpers. When he wasn’t working the land, he returned to his favored trade, carpentry, his heavy toolbox becoming a familiar sight in the neighborhood. He could often be seen walking the road with his sons, carrying tools in one hand and a sack of flour over his shoulder.

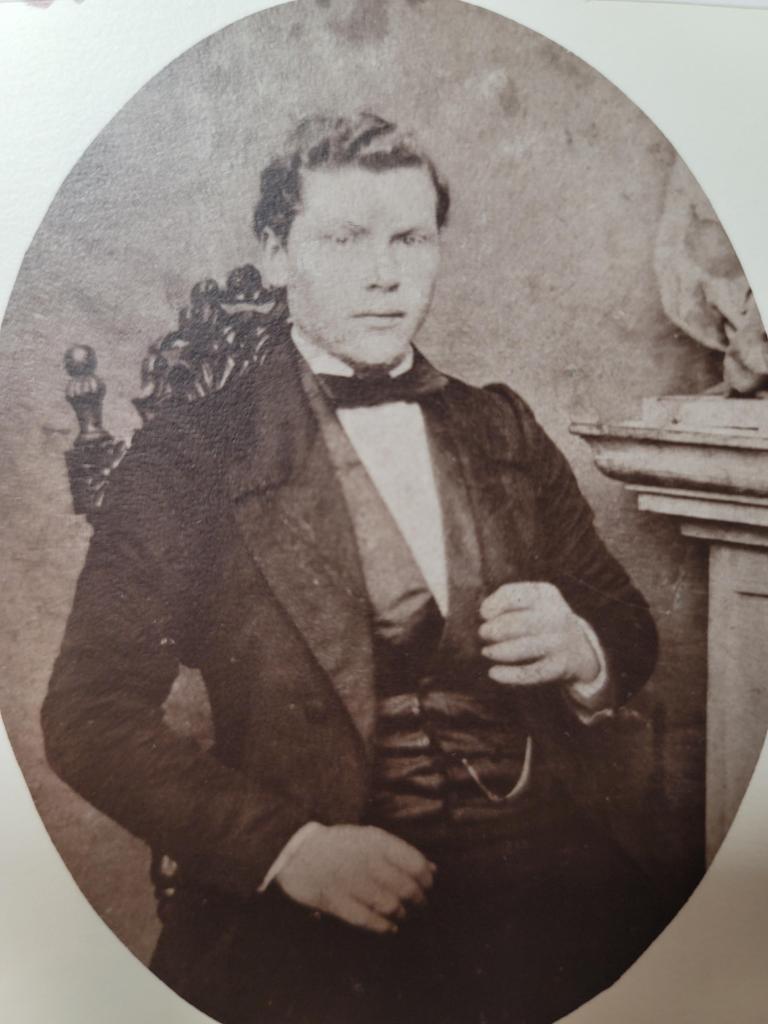

Photograph: Jacob Olsen Aase

Jacob’s skills as a builder quickly earned him a reputation in the community. He constructed windmills that spun gracefully in the prairie winds and barns that housed livestock through frigid winters. But it was his work on the first Salem Lutheran Church in Radcliffe that became his legacy. Jacob was summoned to the work by his reputation – word had gotten out about the training he’d had under the incomparable Fritz Von der Lippe in Stavanger. An offer was made for his expertise, and he answered the call.

Jacob poured his heart into the project, crafting every detail of the small community church that would serve as the spiritual center of its community. The altar became his masterpiece. Carved from local wood, it reflected the simple beauty of the prairie and the deep faith of those who would kneel before it. He took weeks to carve its intricate Gothic-inspired details – chiseling the delicate crosses adorning the top, and molding the deeply inset arch centerpiece which contained a painted depiction of Christ ascending into heaven. The entire piece brought a sense of divine presence to the humble space. When it was complete, Jacob stood back and admired his work, enormously pleased. Though he couldn’t have known that the altar would still be in use more than a century later, he understood that he had built something meant to last. It was more than wood and nails—it was a symbol of faith, community, and the life he and Frederikke had built together.

Jacob’s altar, still in use at Salem Lutheran. Credit: Salemlutheran-aflc.org

The Carpenter from Stavanger

In later years, Jacob and Frederikke continued their migration North to Minnesota so that they could stay close to their children and their families. Their sons lived exciting and full lives of their own and Jacob and Frederikke desperately wanted to be a part of it all. When Jacob passed away in 1913 at the age of 76, he left behind more than a family—he left a legacy of craftsmanship and a spirit of adventure. Today, Jacob’s story lives on in the records he left, the altar he built, and in the descendants who continue to tell his tale.

Coda: This story is embellished but based on actual stories passed down in the family and documents left behind in genealogical and historical archives. You can read more about this website here: About the Site

Leave a comment