The year was 1917, the war effort was on, and the lead mines of Picher, Oklahoma, had never been in more demand. Christopher Columbus Maples took a deep inhalation of the cold air outside the mine shaft, surveying the view of the massive chat piles which to him always resembled sand dunes in faraway places he had once dreamed of, but knew he would never see. With a final look at the lavender sky, he turned to enter the creaking metal cage that would bring him to his work for the day. The air inside the mining shaft was stifling, stinking of rusted metal and the body odor of the hundreds of men who crowded the tunnels to do their work. The fresh breath he had taken was already fading as he rang the bell for the hoist man to lower him down. As the air became thicker with dust, his irritated lungs raged back against him, and he coughed, eliciting a sympathetic look from the foreman. Unbeknownst to him, an unseen enemy, mycobacterium tuberculosis, had already staked its claim on his lungs, setting him on a course that would one day consume him, just as the mines themselves would someday consume the town of Picher.

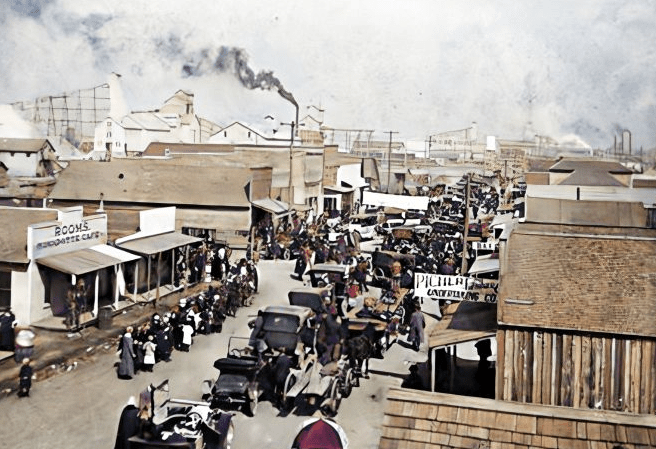

Picher, Oklahoma, located about 25 miles southwest of Joplin, Missouri, was an essential source for zinc and lead during the early 20th century. The mines fueled both the industrial boom and America’s military efforts in World War I, with the “Anna Beaver Mine” and others in the area producing over 100,000 tons of zinc and lead between 1917 and 1928. Zinc and lead were, of course, indispensable for galvanizing steel and iron, protecting military vehicles and naval ships from corrosion, and providing key ingredients in bullets and other ammunition. However, the relentless drive to fuel the war machine came with devastating consequences. The Quapaw Nation, who by many standards were the rightful stewards of the land, saw their territory ravaged, its natural beauty sacrificed for economic expansion. Meanwhile, the miners themselves were exploited and paid a steep price, as the Tri-State Mining District recorded the highest rate of tuberculosis in the country, the deadly silicon dust and lead lingering on as a silent but pervasive threat.

Christopher Maples’ life mirrored the burdens of the mining industry; he felt the physical strain, the emotional toll, and the fractures it caused in his family and body. As illness and exploitation took their toll, Christopher struggled to remain resilient. Despite the many hardships that plagued him, he was determined to rise above the dust and reclaim a life of dignity and purpose.

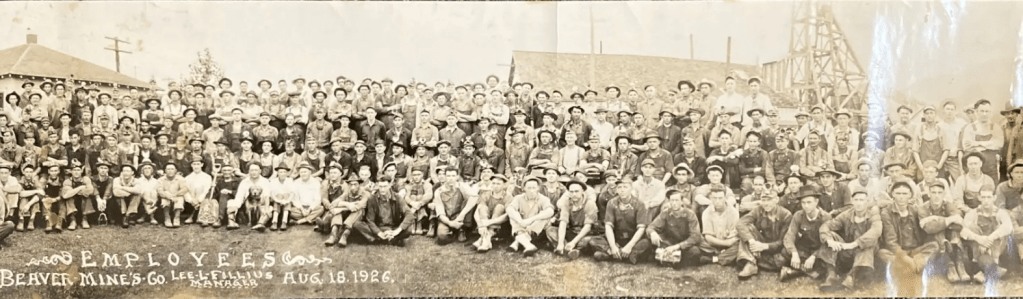

Anna Beaver Miners of Picher Oklahoma: 1926 (source)

Carving a Path: Christopher’s Early Years and Choices

Just south of the Tennessee River lies Morgan County Alabama, where Christopher was born in 1875. The local families were mostly farmers, tending to land that seemed to stretch endlessly along the travel-worn river banks. Christopher’s father was a farmer, too, but also a salesman, and he spoke often with his three sons about how to make a living by meeting the neighbors and providing the goods that they might need. Christopher’s brothers, Jonas and William, happily pursued sales as a family trade, but sales simply didn’t hold Christopher’s interest in the same way. He wanted a different kind of life, and when he read about an opportunity to go make a great wage working at mining silt for paving bricks in Texas, he said goodbye to his parents and boarded the train for a new adventure.

That adventure was waiting in Texas, not only in the form of mining work but also in the bright, hopeful smile of one Miss Josephine Clark. Their marriage, though brief at just nine years, brought them two children and the fleeting promise of a stable family life. But the realities of mining work took a heavy toll; grueling, backbreaking labor left Christopher with little energy or joy to bring home to his family. But Christopher stuck at it, determined to provide. As time wore on, he grew disillusioned with the trade, finding it far more exploitative and far less rewarding than he had once imagined. His first marriage was left in ruins in very short order, though he quickly moved on to another relationship, hoping to piece together something resembling a normal marriage.

But this second marriage, to a widow with six of her own wayward children, was over even faster. Despite attempting to change to different mining operations – first to a coal mine in Wood County, Texas, then on up the map to Picher, Oklahoma to work in the Anna Beaver Mines, boring for lead and zinc – it remained too difficult for Christopher to hold up his end of any marriage bargain. By 1916, the marriage was officially over, and Christopher’s health was declining. And so he wallowed in unhappy bachelorhood in the Joplin, Missouri area, trawling the neighborhood’s night haunts between jobs. The Anna Beaver Mine, which had at first offered so much promise in the form of steady pay, was beginning to look like an unappealing gig indeed. It was there, in the tunnels of Picher, that the dust of his twenties and thirties finally caught up to him. As Christopher sweated alongside the other miners, the invisible enemy – the “White Plague” – settled into its new home in his lungs.

Picher, Oklahoma in the 1920s (source)

A Caged Canary: The Doomed Marriage of Christopher and Daisy

It was early in the year 1916, and Christopher was a man trapped – by circumstance, by the miner’s cough getting worse each day, and most of all, by his own inability to find a way forward to a stable life. The damnable mines had become his cage, each descent into the suffocating tunnels tightening the chains around his ankles. But like the canary in the proverbial coal mine, Christopher had one last melody of hope waiting in the form of a young woman he met in a Joplin church, Daisy Pearl Sanders.

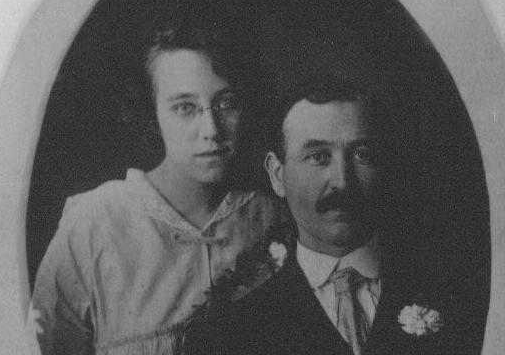

Daisy was unlike any woman Christopher had met before. She was enormously practical – intelligent and hard-working, with a self-directed sense of purpose that clearly came from her mother Nellie. She’d been brought up in a strict Baptist household and had an enduring sense of propriety, so Christopher knew that he would have to wed her if he wanted to create a life with her. He hesitated before proposing – she was twenty years his junior and he wasn’t sure he wanted to get married for a third time. But she was gorgeous, a brown-haired darling of the Jazz Age who appreciated music and the night life and held the promise of a future full of love and laughter. Before the year was out, they were wed, and she quickly pulled him into dreams of their life together with two young angelic daughters, tiny versions of Daisy herself.

But the joy didn’t last, and Christopher’s need to escape the treachery of the mines interjected itself at a terrible time. The income was no longer enough to sustain the life that Christopher had dreamed of, and the tuberculosis that had taken hold of his lungs was creeping its way around to consume the rest of his body, mind, and energy. He had many heated arguments with Daisy about leaving the mines, but she seemed disappointed that he had no clear plan moving forward. They had mouths to feed, and there was only so many times that they could crash on Nellie and John’s couch before they might be forced out to the streets. Daisy grew increasingly resentful of his inability to make the life she’d dreamed of, and each day he descended into the mines in Picher felt like a step closer to his own grave.

And then, one night in the dead of winter, Christopher simply gave up. He’d had another string of arguments with Daisy about money, and he honestly had no idea how to make it right. As the evening drew to a close, he retreated to their bedroom and locked the door. When Daisy checked on him a few hours later, she got no response, despite increasingly frantic attempts to gain entry. After forcing the door, she found the room empty. The window was ajar and his suitcase was gone – Christopher had escaped into the night, leaving Daisy and their daughters behind without a word of explanation. Christopher, the caged canary, had flown. Just as the mines in Picher had ravaged the land and left behind its wake an uninhabitable ghost town, Christopher too had whirled into Daisy’s life and left destruction in his wake – a series of decisions he would come to regret for the rest of his too-short life.

Daisy and Christopher on their wedding day, 1916

A Light at the End of the Tunnel: Maples Grocery

Christopher was adrift after leaving Joplin. With three ex-wives and four sidelined children, he felt himself to be a bit of a failure. His fifties were upon him, and he felt he had spent his life working himself into an early grave without much to show for it. Defeated, he made his way to Texas, where his brother Willy had been working successfully as a butcher for twenty years, taking after their father’s interest in food sales work. Christopher envied the easy, steady life of Willy, who had a solid marriage and home life. Christopher’s nephews even seemed happy – and why shouldn’t they be? They woke every morning to the cheerful sounds of their parents having coffee and had the pleasure of their father’s company every evening – no coal miner’s dust to avoid when they hugged him, and the icebox always had food inside.

One thing had to be said for Christopher – he kept pushing for that good old American dream. It wasn’t long until he put his new vision into action, marrying for the fourth and final time to Della Hodge, an older woman with a reputation for being a bit grouchy, but who was nonetheless practical and good with keeping books. She would be a perfect partner for a small grocery business. Together with Della and her granddaughter Roberta, who she was raising, they moved into a small red-brick building abutting the modest grocery store he would run until his own time ran out.

Unfortunately, Christopher didn’t get much of a chance to live out his dream. He was married only a short time before the echoes of the mines and the scars of his labor underground finally took their toll on his body. The “White Plague” and “Miner’s TB” was also known more broadly as “Consumption,” and consume his body it did. He spent years wasting away in bed, trying every kind of medication and treatment the doctors had at the time to reduce the suffering and misery his cough was putting him through. But a cure for TB was more than a decade away, and in the summer of 1934, he finally, quietly succumbed. His obituary recognized him as the “Belton Grocer” and made no mention of the decades he had spent in the Picher mines, nor for that matter of the beautiful daughters he had abandoned a few short years before in Missouri.

In the end, Christopher Maples was a man whose life was shaped by the dreams he chased, the hardships he endured, and the family he longed to build but could never quite figure out how to create. Though his life in Texas was brief and shadowed by illness, the small grocery he built with Della became a quiet testament to his resilience – a man who never stopped striving for a better life, even when it felt just out of reach. His journey, though punctuated by failures and regrets, stands as a quiet echo of the American dream: flawed, complex, and ultimately human.

Coda: This story is embellished but based on actual stories passed down in the family and documents left behind in genealogical and historical archives. You can read more about this website here: About the Site

Read more about Picher Oklahoma, TB, and the Quapaw Land:

https://www.academia.edu/23234584/Tri_State_Mining_District_legacy_in_northeastern_Oklahoma? – Discusses the high rate of tuberculosis in the district.

Urbex Underground: Picher, Oklahoma Ghost Town – Historical context on Picher and its environmental disaster.

5News: Picher, Oklahoma – The Biggest Environmental Disaster You’ve Never Heard Of – Details on Picher’s status as an EPA Superfund site and its toxic legacy.

Harvard: Tuberculosis in Europe and North America (1800-1922) – Historical overview of TB and its prevalence in mining communities.

SHS: Report on Anna Beaver Property – Historical insights on the exploitation of Quapaw Nation lands for mining purposes.

Leave a comment