The Man at the Desk

Glenn Hastie Mitchell was a busy man. He gestured to the young man who had just walked through the doors of the employment office to take a seat with the others. The waiting area for men seeking jobs was crowded, and conversations were lively. Most of the men were talking about the bank robbery that had happened across the street a couple of weeks before – John Dillinger’s gang – and wondering how it would impact their own meager accounts. It was April of 1934, and the great depression was fully underway. A metal fan on the windowsill creaked, pushing the stale air around as the men talked. The office itself felt as upended and disorganized as the lives of these job-seekers – stacks of applications, ledgers, and daily newspapers littered every corner and counter space available.

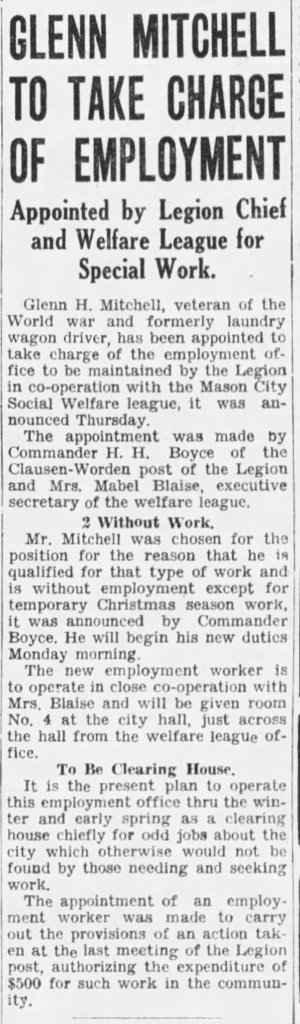

Glenn took stock of the crowd waiting for him while he grabbed up the ringing phone. “Mitchell here,” he said with authority, and listened for a moment to the caller. It was another reporter from the Globe Gazette, wanting updates on the community garden initiative. He promised to call back and turned back to the men who were waiting in the office front. The room smelled of cigarettes and body odor. These were working men without work, and the desperation and humiliation were apparent in the way their shoulders were slumped in defeat. The Million Job Effort by the government had been a way to restore hope to the unemployed masses – and it was Glenn’s job to make sure everyone found something to do. He ran a calloused thumb over the framed picture on his desk; it was an outdoor portrait of him and his father Owen on their family farm. Glenn had spent his childhood watching his father fight for what was fair and right, refusing to let big buyers undercut the value of honest labor. That same sense of justice sat in Glenn’s soul. He believed in a job for everyone, and when he proposed to the Mason City employment office that there was enough work to go around, they were skeptical but willing to let him try.

“Alright, fellas,” he said to the room, standing and straightening his tie. “Let’s see what we can do with you.”

Steady Work

The gentleman who stood to shake Glenn’s hand had the sorriest expression Glenn had seen in quite some time. He looked like a man who had lost more than just a job. He stood ramrod straight and spoke with a clipped, polite manner that was familiar as apple pie. This had to be a military man. Glenn motioned to his desk and sat, picking up a clipboard and fixing a fresh piece of paper to it for making notes.

“Name?” he asked, not unkindly.

“Robert Christiansen, sir.”

“You a vet?” Glenn asked, scratching a note with his pencil.

Christiansen did not hesitate with his answer. “Yes, sir. 351st infantry.”

Glenn looked up and met the man’s eyes. The face that greeted him was unsmiling but patient. “France?”

Christiansen’s chest rose and fell with a deep breath. “Yes sir. Argonne.”

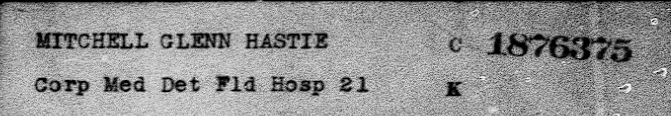

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Glenn didn’t need to ask for details. He’d been there too. The memories still flashed in his mind on an almost daily basis – war changed a man. He could smell the odors of the bodies crammed into his medical tent in Field Hospital 21, the urgency to stabilize patients before they could be evacuated to larger facilities. He tried not to remember the groans of agony as he knelt in filthy conditions, cleaning and bandaging wounds as best he could with the limited supplies they’d had with them. He had been a corporal, barely older than the men he tended, but he’d done the work without complaint, because it had needed to be done.

Glenn mentally sorted through the jobs he had available to give out. There weren’t many. A wealthy family had offered some yard work on a part time basis. There was a diner nearby looking for help. And he’d gotten a call this morning – yes, that could work.

“You know the freight yards?” Glenn asked, rifling through his desk drawers for the information.

“Rail work?” Christiansen looked interestedly at the flier Glenn had been working on.

“It’s not easy, but it’s steady work. Should have enough for you for at least a month. Then you can come on and see me again, ok?” Glenn patted the man on the shoulder as he showed him the door. He watched the soldier march down the street with his shoulders up, renewed in hope and purpose. Glenn’s heart soared for a moment, but then he turned and saw the crowd in the waiting room. He’d helped one man today. He had to remember that he was doing his best.

“Okay,” he said, his voice clear. “Who’s next?”

The Woman in the Yellow Dress

The woman who sat across from Glenn next had a professional air about her. She was dressed primly in a modest yellow dress that had been obviously patched many times over but was freshly starched and ironed. Her shoes were worn thin – she’d been walking around a lot, maybe knocking on doors looking for work. Glenn had seen too many men crumble under the weight of the Depression. Women like this, though – he had to admire a woman with pride. They held the world together while it fell apart around them.

“Name?” he asked kindly, pencil poised.

“Laura Gray.”

He nodded. He thought she seemed familiar – maybe she lived nearby. There was a boarding place over on Federal Avenue near his own house, and he thought a few divorcee’s with their children maybe lived there. She was obviously doing her best to provide.

“What’s your trade, Mrs. Gray?”

The woman spoke without hesitation: “I taught school before I was married.”

Glenn nodded. That made sense. Schools had been letting go of teachers left and right, and tended to keep on the men before the women.

“And since?”

She clasped her hands in her lap. “Clerk work. A little bookkeeping.”

Not a widow. Not exactly. Glenn glanced at her left hand. No ring, but a pale band of skin where one had been.

She noticed him looking. “I was married,” she said without any hint of shame, looking him straight in the eye. “My husband left last fall. No word since.”

Glenn tapped his pencil against the desk. That, too, was something he’d seen before. A man loses his job, loses his pride, and one day, he just doesn’t come home. Too many women all over Mason City were struggling to feed and clothe children who didn’t even know their fathers.

Almost unwillingly, Glenn’s gaze drifted to the framed photo on his desk—his daughters – Dorris, Lorraine, Joyce – now young women. His gaze focused on Dorris, his oldest child. She had been born while he was in France, bandaging men who wouldn’t live to see the morning. By the time he returned, she was already walking and talking. She was a stranger to him. His wife, Ada, had raised her alone for those first years, but had relied heavily on her own family, often leaning on them to take Dorris when it all felt like too much. It had changed their relationship in ways he couldn’t fully understand, and even though he tried, he could never really bridge the distance again.

Glenn straightened, suddenly remembering he had a job to do. “I won’t lie to you, Mrs. Gray. Teaching jobs are scarce.”

She nodded. She knew that, or she wouldn’t have come.

A diner near the train station was hiring. “Ever done serving work?” he asked, holding up the notice.

Laura’s lips pressed together, but she nodded. “I can learn.” She looked down at her hands, folded in her lap in a silent prayer. She’d wanted a job. The hours would be long and the clientele may be rough. She sighed. “I need work, Mr. Mitchell. I’m not too proud to take it.”

Glenn thought of Dorris, shuffled between grandparents and parents. Stability had come late for her – too late to close the distance between them. This woman just wanted something steady so her kids could stay close. Maybe for Mrs. Gray’s children, it wasn’t too late.

She reached for the job slip. “Thank you, Mr. Mitchell.”

Glenn shook her hand. As she left, he watched the way she stood taller now. Some jobs weren’t just about money. Some were about dignity. About keeping a family whole. He took a deep breath, looked at the next person in line, and beckoned them to come.

Dorris, Lorraine, and Joyce Mitchell (date unknown)

The Harvest

The line of unemployed Iowans kept growing without an end. Day after day, men and women filed in to talk with the man who had taken on the task of finding everyone a work match. They all carried their own burdens, and Glenn tried to help where he could – a clerk job here, an odd job washing windows there – but there were always more workers looking for a way to make ends meet than what he could manage. It was never enough. Even with the Million Job Effort and support from the city government, there were so many hands left empty, families on the brink of starvation.

Glenn had to think bigger. He’d spent his childhood on a farm, watching his father reap the benefits of hard labor in the fields. He knew Iowa had vast tracts of underutilized farm land, and he had the spark of an idea. Maybe the city would let him use some of the land for a community garden, one where some of the unemployed could work and all of Mason City could feed their families with the food grown there.

And so, Glenn’s most ambitious project began. He first had to get the American Legion commander, H.H. Boyce, and his executive secretary to sign off. He spent weeks developing a pitch, and when it was ready, he went in to make his case. At first, he encountered dubious resistance. The vacant lots he was spying were spread across Mason city – unused land near Elmwood Cemetery, empty fields by the fairgrounds, and abandoned property no one had touched in years.

“Mitchell, you think folks are just go out and farm a graveyard?” Boyce heckled him from around the cigar that was always dangling from his lips.

But Glenn just shrugged and kept pushing forward, finally gaining permission on the condition that the project’s success be monitored closely. He set up a municipal canning kitchen and immediately found some locals to work it. He arranged for families to tend to their very own plots, and he turned barren land into productive gardens. He camped out on and patrolled the land like a security guard after he found evidence of theft, shotgun in hand. He wanted to make it clear that if a man wanted to eat, he should earn it through hard work. The thefts soon stopped.

By winter, over 100,000 cans of food had been preserved for Mason City’s unemployed families. The program had been a resounding success, making something out of practically nothing – and this time, nobody had to beg for meals or work. He was proud of what he’d done with this work – it was a way to give back what the depression had taken. A way to make sure that families stayed together, that children didn’t feel like burdens, and hunger didn’t force people apart. It wasn’t about the wages – it was about the dignity, the survival. It was about building something that would last. The harvest of the work had arrived.

Glenn took one last look at the rows of crops that stretched toward the horizon, and turned to walk back towards town. His work wasn’t done yet, by half.

Coda: This story is embellished but based on actual stories passed down in the family and documents left behind in genealogical and historical archives. You can read more about this website here: About the Site

Leave a comment