Reverend Harper wheezed heartily as he climbed the hill onto Ninth street, pulling out a handkerchief to sop up the sweat that was collecting unrepentantly on his brow. The summer air was stifling – Leadwood Missouri was as prone to the miserable humidity of summer as the other areas of the state, but the people of the old mining town never complained. Today he was paying a visit to Myrtle Edith Roney, a member of his East Side Church of God for decades. It was the 1960s and house calls from clergy weren’t as popular these days, but Myrtle was in her 70s now and had been insistent on staying home. “I’ve got terrible blood pressure, Reverend, and I don’t get out much these days. Can’t you come by?” And so he had locked up the church and started on foot up the hill. Her house, a modest single-story bungalow with a gabled roof and small front porch, was less than a mile away from the church and he needed the exercise.

“Come in!” Myrtle hollered when he knocked on the screen door, which offered a clear view into the dining room. The door had obviously been left open to help the fan circulate some of the hot air out of the house. From where he stood, he could see Myrtle’s sister Halie moving around the kitchen, an apron tied around her waist as she pulled soapy dishes from the sink. He came inside to find Myrtle sat at her dining table, surrounded by piles of photo albums, shoeboxes, yellowed newspaper clippings, and various trinkets and items. She appeared to be organizing the items into four or five neat piles.

“She’s been at this all morning,” Hallie said, wiping her hands dry on a dish towel.

Myrtle chuckled at her sister. “I’m getting things in order,” she explained, waving Reverend Harper toward a chair. The house smelled charmingly of freshly brewed sun tea – and at Hallie’s insistence, he poured himself a glass before settling down to talk with her. “Here, make yourself useful,” she said, pulling another shoebox out from under the table and setting it in front of him.”

Reverend Harper chuckled. “What exactly are we doing?” he asked politely as he gamely pulled out a stack of photographs and started flipping them automatically to the back to read the ink-stained labels that indicated who he was looking at.

Myrtle put down the item she was holding – an engraved guitar pick she’d been studying – and sighed. “I don’t know, Harper. It just feels like my days are numbered, you know? I’m gettin’ old. I figured I better start going through this stuff and figuring out how to divide it up. That pile there’s for Cliff, and here for Agnes. If you find any musical stuff we’d better put it in Delmer’s pile here. And there’s Jim, and there’s Roy, ok?” And without any further explanation, she dove back into her own shoebox. Inwardly, the Reverend smiled. She clearly wanted to talk about dying, but it seemed like maybe she couldn’t quite figure out how to ask. This happened sometimes with his parishioners. It seemed like he could bring the comfort they sought out just by sitting with them and reminiscing. He would play along.

The Heart of Viburnum

“So, Myrtle, what’s the plan here? Photos to Agnes?” He handed over an ancient, weathered photograph of a storefront, its edges worn down with years of handling. Myrtle took the photo and adjusted her gold-rimmed glasses, raising her chin as she held it at arm’s length, the way she always did now since age had stolen the sharpness from her vision. Recognition of the photo’s subject spread on Myrtle’s face like the dawning of a morning sun. She smiled warmly as she tried to make out the figures so she could point at each one.

“That’s the Mincher’s store,” she explained, showing the photo to the Reverend. “I worked for them when I was a little girl. Me and Chuck and Lettie, we practically lived there. That was the heart of Viburnum, where we grew up. J.C. Mincher was the town doctor and his wife Laura helped us get a post office, which ran right out of that store! On the left there is Eura, who married Chuck, and then Dr. Mincher and Laura, and that’s their son there with the guitar. And there’s me and Chuck.” She stared at the photo for a beat. “I loved my brother. He died so young, when that flu came through in 1918. I named my first son Charles after him, but he’s gone now too. Bad heart.” She put the picture down and closed her eyes, taking a few deep breaths as if fortifying herself. Reverend Harper leaned over and patted her shoulder. He knew it was hard coming to terms with one’s own mortality.

After a minute, Myrtle smiled gently at the Reverend and dropped the photo into Agnes’ pile as he’d suggested. She turned back to her shoebox. “You know, I think I kept something…where is it…” after a moment of concentration, her eyes lit up. “Here!” She pulled out a small black suede-covered ledger book and the spine cracked as she lay it open on the table in front of her. The pages were filled with neat cursive, listing names of customers, item costs, and delivery information; it was a perfect capsule of her years of work at the Micher’s store. She opened it carefully, running her finger over the names.

“Look here, there’s Pa! Moses Payne,” she read carefully, pointing to an entry. Her father had been a farmer and often came to the shop to barter crops for goods. “And I’ll bet I can find Frank in here.” The Reverend knew that Myrtle desperately missed her husband Frank, who had died tragically some twenty years before. He cheered along with her when she finally found an entry with his name, and sat back in his chair, happily sorting through another stack of photographs from his own shoebox.

“Frank was a good man,” he said to Myrtle.

Myrtle nodded, pressing the ledger shut with a gentle finality. “The best,” she said.

Precious Memories

The clatter of dishes reminded the Reverend that Hallie was still at work in the kitchen. He smelled the sausage before he heard the sizzle of it in the pan, and his stomach rumbled in acknowledgement that breakfast was coming. Hallie plunked a plate down obligingly in front of him. “You’re too thin, preacher. Eat up.”

Harper grinned and tucked in. “You don’t have to tell me twice!” he said appreciatively as he began to eat, still sifting lazily through photographs with his left hand.

Myrtle, annoyed, pulled the photos out of Harper’s hand and rubbed a spot of grease off with her sleeve. “This isn’t your diner, Hallie, now would you two take this seriously?” Hallie and Harper laughed good-naturedly and watched Myrtle as she continued her quest. She had pulled out a folder labeled “Old Tax Papers” and tapped it firmly on the table, as if to rid it of spiders and dust mites.

Hallie reached for the top paper and turned it over to inspect the date. “1948! Myrtle, why on earth do you have tax papers from so long ago?”

Myrtle made a waving gesture with her hand and said “You never know when the government is going to come to call!” She shuffled through the old land deeds and receipts, and explained further. “We had a good farm once, with a hundred head of cattle, down by Hutchins Creek. I might have a photo in there if you keep digging. Those were the good years, with all my kids. Frank taught the boys to fiddle and we used to sit out in the backyard after the farm chores were done for the day and celebrate with some music.”

Hallie smiled fondly at her sister. “Do you remember how excited Frank was when he got that music teaching job up at the school?”

Myrtle clasped at her chest dramatically and closed her eyes in pleasure at the memory. “Ah, it’s too bad we had to leave.” Her foot was tapping rhythmically as if she was hearing the music in her mind.

Reverend Harper broke into her thoughts. “What happened?”

Myrtle sighed. “Oh, you know, same thing happened to everyone during the depression. We couldn’t sustain it. But the mining companies were coming around, so we all came here to Leadwood to make our living. It worked out ok.”

Just then, the front door creaked open and Myrtle’s daughter Agnes swept in, flapping her blouse to help cool herself off from the heat. She was a beautiful young woman of forty, and her eyes swept the room quickly, taking in the scene and quickly getting the measure of what was happening. She smiled warmly as she made herself comfortable at the table, patting Reverend Harper on the shoulder as she sat.

“It smells good in here. What are you doing with all this?”

Myrtle nudged a pile of photos toward her. “It’s your inheritance, honey! I figured it was time to sort through all of this stuff for you kids.”

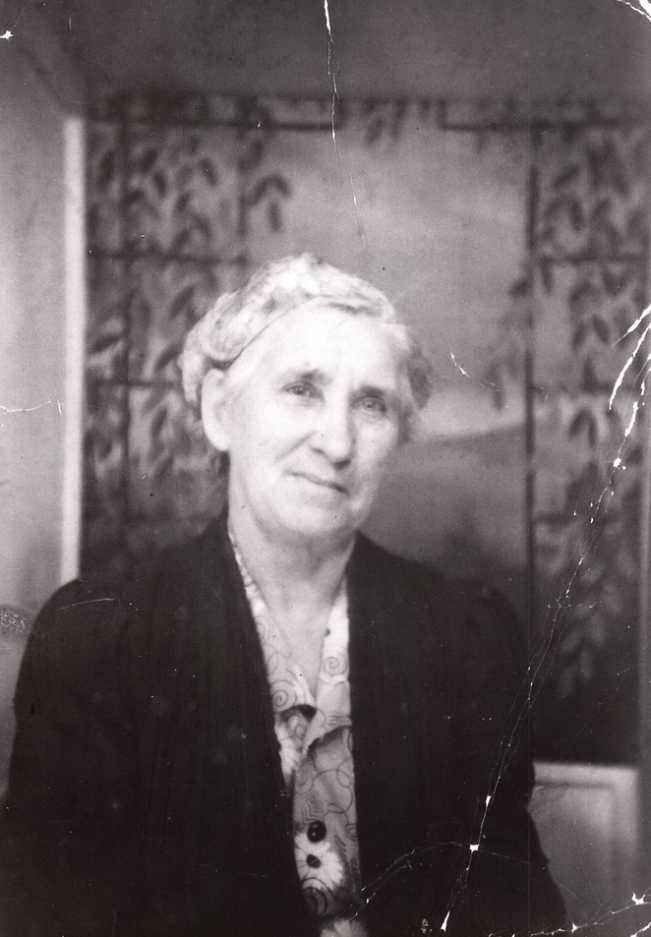

Agnes snorted skeptically but grabbed the photo on top anyway, a black and white photo of Myrtle and Frank sitting formally. “Hey, I’ve seen this before. Wasn’t this from your wedding day?”

Myrtle nodded and reached for the photo to see. “Yes ma’am, we were married at my folks place by Rev. Mincher. We took that picture out back. What else do you have there?” She shuffled through the papers until she found a picture of all of her kids together. “Look here,” she said. “Whose car is that in the back?”

Reverend Harper leaned over to take a look. “Who’s that there?” he asked.

“Oh, let me show you,” Myrtle said. “That’s Wade and Delmar, home from the mines. And then Cliff, in his mechanics clothes. I think that was his car back there.”

Agnes leaned over to see better. “That’s me, I’m waving at Ed. That must have been right after he left his wife.” She rolled her eyes. There was a story there but she didn’t want to tell it now. She quickly pointed at the rest of the figures in the photo. “There’s Jim and Roy. This was I think after the war. Wow, mom, you got one with all of us in it!”

Myrtle smiled but shook her head. “Everyone but little Hallie.” She’d lost a child in infancy to pneumonia. Everyone quieted for a moment. Everything came back to loss. Myrtle grabbed for Agnes’ hand. “It’s okay,” she said.

Agnes squeezed her mother’s hand in return. “I know, Mom.”

What’s Left Behind

For a long moment, the room was quiet, filled only with the distant sound of a cicada buzzing outside the screen door. Hallie finally stood up and wiped her hands on her apron, then started gathering dishes off of the table to bring to the kitchen. Myrtle took a deep breath and tapped a loose stack of papers back into place. “Alright,” she said finally, “let’s keep going. I don’t have all day.”

Reverend Harper chuckled. “Myrtle, I think you have more time than you think.”

She raised a single brow at him in a gesture that had been picked up by every one of her children. “Do I?”

The preacher didn’t answer, just took another sip of his sun tea. He had been doing this long enough to know that when someone was ready to meet the Lord, they were ready and he couldn’t convince them otherwise. The silence lingered, thick with unspoken things, until suddenly Agnes let out a loud sniff, dramatically wiping at her eyes.

“Well,” she said, voice trembling just slightly with irony, “I suppose this means I’m finally getting Mom’s good silver.”

Myrtle let out a surprised bark of laughter, and the tension shattered like glass.

“Agnes, if I’d known that’s all you wanted, I’d have given it to you years ago.” She made to get up and walk comically over to the china hutch.

“Oh no, you gotta hold onto the good stuff,” Agnes teased, nudging the box of old tax papers. “Never know when the government’s coming for you.”

Laughter rippled through the room, and just like that, the heaviness lifted. Agnes leaned over and began sorting through another pile of photos. “Hey, Mom, tell me again about the time Daddy took you dancing.”

Myrtle gave a knowing smile, eyes twinkling just a bit. “Oh, now that’s a story…” She leaned back in her chair, pressing a palm lightly over the worn tabletop, as if grounding herself in everything that had passed over it; family meals, quiet evenings, hard conversations, and laughter had faded and returned again. Outside, the cicadas droned in the Missouri heat. The piles of keepsakes remained half-sorted, waiting. But for now, telling the stories mattered most.

Coda: This story is embellished but based on actual stories passed down in the family and documents left behind in genealogical and historical archives. You can read more about this website here: About the Site

Leave a comment