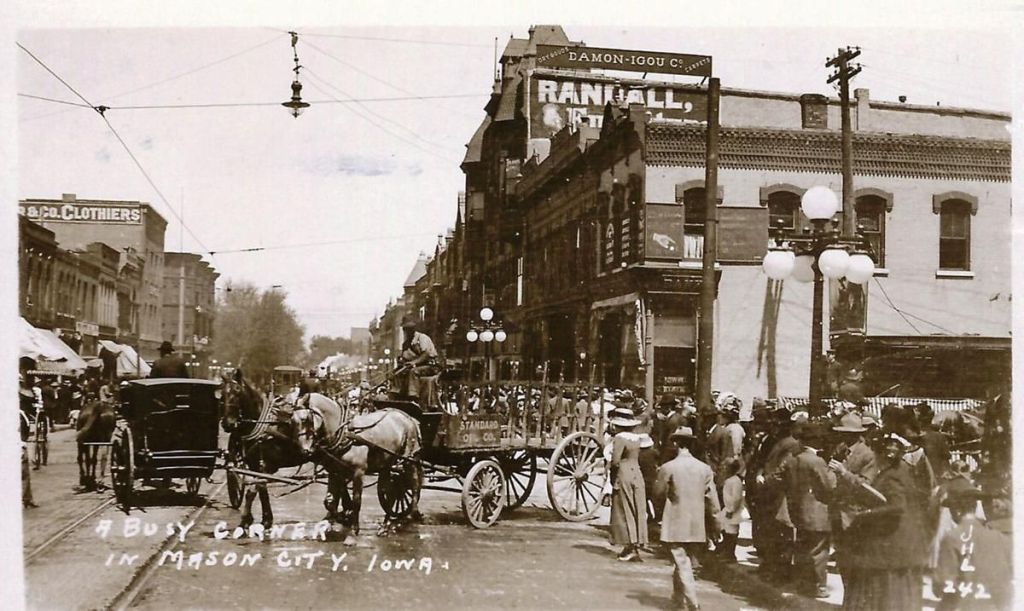

It was April of 1930, and the bur oaks were in full show along the streets of Mason City, Iowa. Eleven-year-old Dorris Mitchell tiptoed into the office room of her grandfather Jacob, curious about the strange clunking noise she’d been hearing coming from there. She was shy, the sort of child who liked to take in a room quietly before saying anything. She was already learning how to keep her family members calm when they got angry or upset, and prided herself on being able to please others.

Jacob S. Miller’s office looked more like a conductor’s museum than a room where any serious business was done. Railroad maps from all over the midwest were tacked to two walls, overlapping at the corners where he’d run out of pins. There was a brass oil can on the windowsill, a cracked lantern on the bookshelf, and a handful of thick leather-bound logbooks stacked neatly by the desk. She could smell pipe tobacco and something slightly metallic, maybe from the old rail spikes he kept as paperweights.

She’d been living there for a little while now, with Grandpa Jake and Grandma Minnie. Sometimes she stayed next door with Uncle Fred and her Aunt who was also called Minnie. So many Minnies in the family. She wished her mom had named her Minnie too, but she was stuck with plain old Dorris. She liked living with her Aunt and Uncle, and she liked her grandparents, too – but she was going back home next week, with her mom and dad. She didn’t know how to feel about that. The Minnies made buttered popcorn and let her read from the Sears catalog for hours, and Grandpa Jake had the best stories from working on the railroads, and growing up in Kansas. At home with her parents, she only ever argued with her mom.

Grandpa Jake was seated at his desk, reading from what looked like an old almanac. He’d been feeling bad lately, and he was kind of hunched over. Dorris’ mom Ada had told her that his failing health was part of why she had to come back home. “We can’t have you over there bothering him when he’s trying to get better,” she said. Dorris never felt like a bother, but she tried to be quieter around him anyway, just in case.

She ran her finger over a framed certificate on the wall, reading it out loud, to show off a little. “St. Joseph & Western Railroad, awarded to Jacob S. Miller…”

“I thought it was called the Grand Railway,” she added, turning to him with a slight squint.

Old Jake looked up from his seat, blinking out of a daydream. “It was,” he said, “but later, after the merger. Grand bought the Western piece of that railroad.”

Dorris tilted her head. “What does that mean?”

Jake leaned back in his chair and pondered his granddaughter. “Railroads eat each other, kiddo. One company buys another, then somebody else buys that one. The name changes, the ownership changes. It’s the same track but a different man calls the shots.”

Dorris playfully pointed at her grandpa. “YOU called the shots?” she asked, crawling into his lap. He chuckled and patted her on the head. He’d climbed the ladder of his career all the way to roadmaster, but he wasn’t a businessman. Owning railroads was for men in far richer conditions than he’d been born to. He told her as much while she climbed down off his lap.

Dorris was looking through the office like it was her last chance, peering through the stacks of yellowed paper by his feet. She was a very good reader, and somewhere in there, she figured, was something else she might want to read. Something with pictures. She found a wooden plaque propped against the bookshelf.

“What’s a roadmaster?” she asked, peering at the word.

Jake smiled and reached for the plaque. “That was me. Roadmaster means I was in charge of a section of track. The men came to me when something went wrong. Broken ties, warped rails, you name it. I’d ride out, take a look, and get it fixed.”

She wrinkled her nose. “That sounds kind of boring.”

“It wasn’t,” he said, and then chuckled. “I had a lot of friends out there and we liked it.”

He reached into the drawer and pulled out a little wooden train whistle, the kind with carved channels that made the old-timey “choo choo” sound. He handed it to her and smiled, relaxing a bit while she practiced with it.

Choo choo, she’d whistle, and then, giggling, she’d sing “I’ve, been workin on the raaaaaaail-road….” Jake let her go on and sing the old tune the whole way through, joining her on the last verse. He got an idea.

“Want to hear a real railroad song?” he asked, leaning in conspiratorially.

She nodded eagerly, clutching the whistle.

“The songs we sang out there, they weren’t like music from the radio,” he warned. “Just call-and-response stuff. Helped the men keep rhythm.”

Dorris thought about that. Call and response. “How does that work?”

Jake stood up and grabbed Dorris under the arms, hoisting her onto his desk so she could be more at his eye level. He could feel a twinge in his lower back with the strain of it – his days of hoisting around his grandchildren were numbered. Aging was for the birds. He looked her in the face and gave her a lesson in railroad chants.

“I’ll start the song by giving you a direction, and then you finish the verse by saying what you’ll do next. So I would say, Pick it up! And you would say “Lay it down!” It helped make the day go by faster and the work didn’t feel so hard. Let’s try.”

He tapped twice on the desk and chanted at her: “Pick it up!”

Dorris grinned and stomped her sandaled foot on his desk, creating a hollow echo, “Lay it down!”

Jake laughed and went on. “Check the tie!”

Dorris thought about what to say back. When she came up short, she sheepishly grinned and shrugged her shoulders. Jake whispered a suggestion at her and she laughed and punched the table with her palms. “Pound the ground!”

They went on like that for a while, his grand baritone and her little alto voice bouncing off the walls. She blew the whistle with gusto, the sound too loud for the room, and they both laughed.

That’s when Ada poked her head in. The doctor had arrived to see Jake, and it was time to get all of her bags packed up and ready to go. Dorris was ushered out, but first she gave Grandpa Jake one last look from the doorway and, with a mischievous glint, called out, “Pick it up!”

He puffed his chest out and shouted, “Lay it down,” and gave her a little salute. Ada frowned and he laughed.

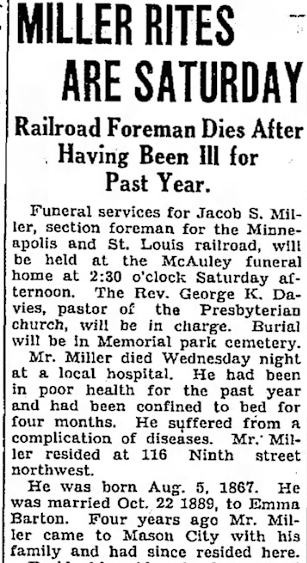

Jacob Miller died that September. Dorris had never been to a funeral before, and she didn’t really know how to feel. She didn’t cry, but she looked solemnly at the slate grey headstone that would mark his burial place, with the dates 1867-1930 carved carefully into stone. It reminded her of the plaque that had been in his office that day he had taught her call and response. Later, every time she passed the railroad tracks near her house, she reached into her coat pocket for the train whistle he’d let her keep. She never blew it – she just held it there, remembering.

Coda: This story is embellished but based on actual stories passed down in the family and documents left behind in genealogical and historical archives. You can read more about this website here: About the Site

Leave a comment