A Labor Day Sermon by the Creek

The Big Huzzah Creek glittered, reflecting the Labor Day sunshine on that day in 1915 when old Sallie Tubbs told the story of the Huzzah Creek Feud. There was a gentle breeze cooling the crowd, who had gathered below the white pines for an outdoor service, directed by Reverend George Asher. He stood behind a wooden lectern borrowed from the Sunday school room in Salem, and contentedly scanned the faces of the crowd, seated in folding chairs and lazily fanning themselves, as he finished up his sermon. Red and white bunting fluttered between two trees near the creek, marking the location of several picnic tables which held a pot-luck feast for lunch.

“As we close our service for the day,” Reverend Asher was saying in a chewy country drawl, “I would like to invite all of you to stay for a while and have some lunch. We’ll be celebrating the 82nd birthday of one of our oldest church members, Miss Sallie Ann Camden. I hope you’ll indulge me a little biography of our Aunt Sallie, as she was a founding member of our community and has much to offer in the way of history.”

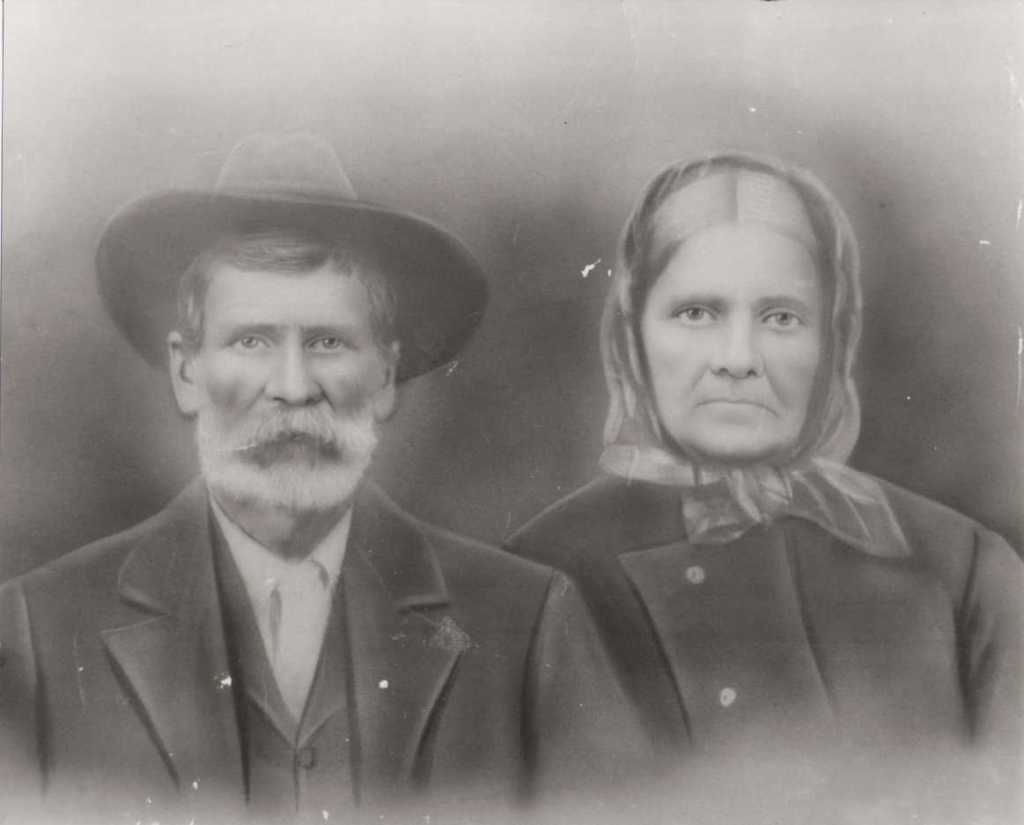

Sallie Ann, dressed in a simple blue dress that fell to her ankles and covered her arms from the chill of any errant breeze, simply smiled and nodded humbly from the seat of honor in the front row. Her sisters Tennessee and Fannie were seated to her left, next to her husband Benjamin, and on her right her sons Milton and Boas reached over and patted her on the arm.

“Sallie Ann’s real name is Sarah,” Reverend Asher was saying, “and even though her childhood was spent in Tennessee with her Tubbs kinfolk, she and old Uncle Benjamin came here to Huzzah right after they were married to help settle this area. She raised a whole passel of Camdens here – eleven children in all – and six of them are here today to help us celebrate.”

Five, thought Sallie, thinking of George in that asylum. But she didn’t speak yet.

“Aunt Sallie and Uncle Benjamin have built a life to celebrate here on Huzzah Creek. If you’ve never spoken with her, today’s your chance! I invite y’all to stay after for cake and conversation. Now let’s have the blessing by brother Barton.”

After Rev. J.T. Barton closed the service and prayed over the food, the congregation quietly pulled their chairs over to the creekside for the lunch. There was much laughter and gentle conversation as Sallie got settled, arranging her hat against the breeze, and soon a beautiful birthday cake was presented. A teenage girl from the congregation handed Sallie a plate.

Sallie thanked her with a warm smile, but she could feel the quiet shift in mood as those sat at her table looked at her. She was expected to entertain the crowd, she thought, but she wasn’t sure what to say. She looked around the table for inspiration, and her gaze landed on her sister Fannie. She smiled.

“Fannie,” she said to the girl, pointing, “is my little sister, did you know?” Fannie grinned, knowing what was coming next. “But did you know that she’s also my step-mother-in-law?” The table erupted with small giggles while they watched the teenaged girl trying to work out how that was possible. After a minute or two of the girl asking confused questions, Sallie let her off the hook. “Okay, here’s how it happened. My husband Benjamin here’s got a father Benjamin Sr. – and when senior was in his sixties, he took a second wife – sister Fannie here.” The girl’s eyes got big and Sallie chuckled. “Well, things were just different back in the old days I guess.”

She looked around for more story inspiration, and her eyes landed on her son Gladden. She told someone to gather the young men around, and when they did, she spoke again. “I don’t know how many of you are going to have to fight in this great war, but I reckon you should meet a hero of our country here – Gladden was in the civil war and fought for our Union with General Sherman. If you ask him, I bet he’ll tell you about the March to the Sea. We are so proud of our Gladden.” Gladden Camden blushed, but promised the boys he would tell them his war stories after lunch.

Sallie could feel the eyes of the crowd on her now, as all the families had started gathering to hear her tell tales of her family. Her eyes glittered with the creek’s reflection. She knew what story she really wanted to tell. This time she straightened slightly and raised her voice, now not speaking just to her table, but to the gathering crowd.

“That road there,” she said somberly, gesturing with her fork toward a tore-up road that ran alongside the creek towards some old dusty houses, “is where the big family feud came to a head. I know you’ve all heard of the Huzzah Creek Feud, but the story is sadder and more tangled than anything I’ve ever seen here in my 82 years.” She studied the faces in the crowd, adding “and a lot of you were right in the middle of it, too.”

The air grew still as if the trees themselves were trying to listen. Sallie’s gaze lingered down the old road, and bye and bye the sounds of the day faded. In her mind’s eye, it was no longer 1915 – she was transported a few precious years back to 1900, to the sounds of the axes chopping, brush being cleared, and the screams of a wound opened by years of family bitterness.

II. Blood on the Trees

Thomas C. Hall Jr. was still a young man when he road into downtown Ironton to file for a land certificate on forty acres in the Red Point territory, Big Huzzah Creek. He quickly built houses for him and for his mother Martha – the only problem being the makeshift road that ran alongside their two dwellings. The Camden and Asher families used it pretty regularly to travel to town, and the dirt and the noise meant that their houses didn’t have that peaceful, easy feeling that he’d envisioned when he chose the location by the creek.

No matter, he thought. I’ll just close this road off and build another, further out. And without first consulting the neighbors or talking it through, he just went about his business. First he built a large fence around the whole property, and put up a sign to tell people to go around. But the Ashers and Camdens didn’t like that, and instead of talking things through, they simply moved the fence in the dead of night, back to the other side of the road they wanted to use.

Undeterred, Tom put his fence back up and designated a new road – narrower, rougher, cutting through a thicket that the Camdens called “hog-worthy” and the Ashers wouldn’t tread on a dare. But the Camdens and Ashers kept to the old road. They stepped over the fence, moved it when it suited them, and when it didn’t, they just shouldered through like they always had.

Tom grew bitter, and Martha egged him on, spurring him to file lawsuit after lawsuit to establish their rights. But the ownership of the actual road was a gray area, and they never got satisfaction from the courts. The Camdens and Ashers pulled in their buddies the Bartons (who had enough strong young men to intimidate an army), and they spent many raucous hours leaning on Tom’s fence, taunting the Hall family, hoping to drive the pests out of town.

Soon, there were fights. Small skirmishes in town, and Jim Asher, all raw muscle and pride, earned himself a fine for giving Tom a shove. It cost him a dollar, but he would pay much more dearly before it was all over.

It was a rainy Saturday in June when Tom decided he’d had enough. He walked out to the dirt road with an axe and started chopping down trees, one by one. He grew more and more satisfied with each “crack” as the trees fell down in the road, blocking travel. It may not look pretty, he thought, but it’ll keep those damn men off my property.

The next morning, Jim Asher was traveling to church on horseback when he came across the fallen trees. Immediately enraged, he gathered some friends and set to work with his own axe, clearing the road of the mess. The men worked for almost an hour, sweating and cussing, before they were disturbed.

Martha came stomping down the yard, hands clenched in the folds of her apron, shouting at them to leave. “You’re on my land!” she hollered. “You’ll answer for this!” But they just laughed at her and kept working. Frustrated, Martha turned and screamed toward the house for her son to come.

And Tom stepped out of the trees. He carried his Winchester rifle in his right hand, the sun catching the steel just enough to blind. The men dropped their branches but didn’t run. They weren’t armed. And Jim was just standing there, holding the horse by the reins.

“There’s that goddamn Jim Asher,” Tom growled. “I’m going to kill him.”

What happened next was disputed heavily by all the neighbors later when the dust settled. Some said that Jim reached in his pocket, as if for a weapon, and dared Tom to go for it. But other said there wasn’t time for that – Tom just took his shot.

One round, tight and cruel, tore through Jim’s chest, just left of the heart. He fell where he stood, twisting against the reins he’d been holding before collapsing into the dirt.

Tom didn’t stop. He reloaded and looked straight at the others, saying “You’re next.”

The remaining men scattered, jumping onto the horse and tearing down the road to get the neighbors and the police. Everyone came – kinfolk, the curious, and the coroner too. They carried Jim back to the Clements’ house. By evening, the coroner’s jury had ruled: Tom Hall had murdered Jim Asher, and Martha Hall had helped him do it. But by then, Tom and Martha were gone, disappeared into the hills of the Ozarks, and the road, covered with blood-soaked trees, ran quiet for a time.

Back at the creek, Sallie’s hands rest quietly on the checkered tablecloth. Reverend Asher had settled next to her while she’d been talking. He was only 35 years old, but his eyes were crinkled with the wisdom of a man who had seen a lifetime of violence.

“Uncle Jim wasn’t no saint,” he murmured to those sat at the table, “but he didn’t deserve to die on the street like that.”

Sallie’s son Milton, now gray at the temples and heavy in the jaw, sat two seats down with a tin plate of beans. He hadn’t spoken since Sallie’s story began, but now he glanced up and met her eyes.

“He thought he’d get away with it,” Milton said bitterly. “But family sticks together.”

Sallie didn’t reply, but she didn’t deny the sentiment either. Her mind was still in 1900, where Tom Hall had vanished into the hills. He was still breathing then, somewhere in hiding, but not for much longer.

III. Revenge of the Vigilantes

The days that followed Jim Asher’s murder were thick with heat and rumor. Tom Hall had become a ghost in the hollows of the Ozarks. Some said they saw him headed toward the Arkansas line. Others claimed he was still nearby, holed up with Martha, rifle across his lap. He wouldn’t surrender, not really, but in late July, he mailed a letter to the Ironton Register, scrawled in a polite, careful tone. It was not an apology, but a challenge to the authorities.

“I will surrender peaceably to the sheriff at any time if I can be guaranteed protection from Jim Asher’s friends,” he wrote. “But I will never surrender to them, not while I have strength to pull a trigger.”

His words sent a chill through Dent County. There was no remorse in them, only defiance. But time, it seemed, was no friend to Tom Hall. By August, Sheriff Gregory had turned up an old lead: Tom had once lived near Jonesboro, Arkansas. The sheriff reached out to authorities there, and two weeks later, Tom was found there and arrested.

“I was going to turn myself in before court anyway,” he told the sheriff. “Didn’t see the point in running forever.” In October, he stood trial in Iron County Circuit Court. The jury found Tom guilty of second-degree murder and sentenced him to ten years in the penitentiary.

The judge, in closing, offered a pointed remark: “Considering the facts in the case, the defendant should congratulate himself upon the mercy of the lower court in not getting a more severe sentence.”

Still, the verdict didn’t hold. The case was appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court, and in the meantime, Tom walked free on bond, stepping back onto Dent County soil with a loaded past and a light sentence.

He was a marked man, and he knew it. He told anyone who would listen that he feared J.T. Barton, Jim’s cousin who had been making it clear around town that he would get revenge. The Bartons, the Ashers, the Camdens – three families with plenty of wild young men who wouldn’t hesitate to carry out their own brand of justice – and Tom knew that they would be beside themselves when they found out he was home free.

It was early fall in 1901 when Tom Hall drew his last breath.

He was working his land, loading corn on a wagon with his brother Charles while his mother Martha chattered at them from nearby. The morning held the kind of eerie stillness that made one shiver. Even the cows were quiet. Tom surveyed his land from atop his wagon while his brother fussed over a wheel. He thought he’d seen something rustle in the bush line a ways off, maybe forty yards yonder.

Suddenly, multiple shots rang out, all at once. A bullet tore through Tom’s chest, exiting right where the X of his suspenders marked the center of his back. In shock, he leapt from the wagon and stumbled a few yards towards where Martha stood, crying out. She froze, taking in the scene. Charles had laid down flat on the ground, avoiding multiple bullets that had come his way, and out of the corner of her eye, she could see dozens of people taking flight from behind the bush line. She thought she recognized a few – there was Milton Camden, and Jim Asher’s brother Chuck, and she definitely saw J.T. and Jubal Barton. But even though she started to chase them down, she couldn’t identify the others, and anyway she needed to tend to Tom.

It was too late to save him. Later, she would tell the sheriff that he had just enough breath left to tell her that he’d seen J.T. Barton pull the trigger on him, and then he died.

Within hours, the sheriff, the judge, and the coroner had held an inquest and rounded up ten so-called vigilantes to lock up in the Dent County jail. 8 men and 2 women spent a long night there being questioned, but every one of them claimed innocence.

Not one of them said a word.

No confessions.

No betrayals.

No names given.

No snitching.

By the time winter came, all ten members of the group had their names cleared. Freed, one by one, to go about their lives. The law had done its part, and the families had done theirs.

V. Sallie’s Advice

The creek had quieted again. The breeze was tugging softly at Sallie’s hat as if nudging her back to the present. The lunch had long been eaten, and the ants were coming out to explore the table tops for crumbs. Sallie’s eyes climbed from the picnic table up to the road, and she gazed into the distance of it, as if trying to see where the bodies of those men had fallen so long ago.

Reverend Asher shifted beside her, clearing his throat gently, but Sallie raised her hand to still him. She wasn’t quite finished.

“Tom Hall was no saint. Neither was Jim. And Lord knows our Milton didn’t keep his hands clean either. But those were our boys. ALL of ‘em. Folks back then, they did what they thought they had to do. And maybe they did have to do it, but blood – “ she paused and thought carefully before proceeding – “once it’s spilled, blood don’t ever really wash out all the way, you know? It just dries and stays there as a reminder of the mistakes you made. I mourned Jim, just like everyone else around here. But what came after… what folks whispered and what they did… it tore this place worse than any bullet ever could.”

She lifted her hand slowly, pointing. “We went on using that road for a long time, but every time I crossed it I wondered what if you boys had just sat down and talked it through, right at the start? The sheriff let it go, and most folks around here did too – but don’t ever thing it didn’t amount to nothing.”

With that, Sallie stood, brushing her skirt of crumbs.

“Now,” she said brightly, “somebody go fetch me a second piece of that cake. A woman ought to eat like she plans to turn ninety.”

Coda: This story is embellished but based on actual stories passed down in the family and documents left behind in genealogical and historical archives. You can read more about this website here: About the Site

Leave a reply to alexander87writer Cancel reply